Bike Trip!!!

It was the fulfillment of a dream. It was a test of endurance. It was an ultra-fun series of daily adventures. It was, sadly, too short. (Spoiler alert!)

For years I had dreamed of a long journey by bicycle. I live in Durham, NC, and I don’t own a car; I bike everywhere. Sometimes I’d ride home at the end of what was then, for me, a long ride, to Chapel Hill, say, or to the end of the American Tobacco Trail (round trips of 30 and 50 miles, respectively), and I’d think: What if I kept going? Could I bike 2,000 miles to Tucson, my hometown?

I made vague plans to take this trip in 2018, when I left a salaried job and started working as a freelancer. But I didn’t yet have the resolve to actually do it. When the coronavirus hit in 2020 and my work dried up, I thought: Now’s the time!

Planning

My plan started to percolate when I took a trip with friends to El Salvador in the Summer of 2018. In the town of Santa Ana, we met Natalie, who bills herself as the first transwoman to bike the Pan American Highway, which runs from the top of Alaska to the bottom of Chile. Her horror stories from the road, like how she was wet for the whole first month because it wouldn’t stop raining, or the time she had to carry her bike over a small mountain and ended up drinking her urine to rehydrate, only made me more intrigued—I relish stories about overcoming adversity. And she was very encouraging. She showed me her bike and gear and gave me lots of useful advice.

Then, last year, I met my current roommate, Steven. In 2008, he’d biked from his home in Cary, NC, to California. He shared his blog from the trip, and told me what tools, bike parts, clothes, etc. I’d need to bring. He laughed when I showed him the bulky camping gear I’d bought on sale at REI. On his advice, I went online and bought a tent, sleeping bag, and pad that weigh a total of five pounds.

My final trip advisor, the one who really made it all possible, is my friend Jacopo. He leads bike tours for a living, and for a hobby he builds bikes for friends. Most touring cyclists buy specialized bikes with lots of attachment points, a long frame, and a low center of gravity. Jacopo offered to build me a touring bike; I told him I was hoping to use my beat-up old 1996 Trek steel-frame hybrid, which I had gotten for free at the Durham Bike Co-op a few years ago, because it fits me so well, and because, well, I love it. He liked my approach: “Some people get so into the gear,” he told me, “it’s like, why don’t you let the gear take the trip, and you can stay home?”

If my rusty old jalopy of a bike was going to be cross-country road-worthy, it would need a lot of work. Jacopo got me set up: new cassette, cranks, cables, rear shifter, rear wheel, chain, spare chain links, water bottle cages, foldable tire, mini bottle of chain lube… thanks to him, I was ready to go.

The Plan:

West-east route

Dec. 5: Fly to LA and stay with my sister Hannah and her family in Glendale

About a week later: Start journey!

Try to arrive in Tucson in time for a (distanced) Christmas with my father and stepmother; if I’m going too slow, Hannah, her husband Mike, and my nephew Linus would pick me up on their way to Tucson on Dec. 22nd

Stay in Tucson a couple weeks

Ride to Bisbee, AZ, to see my friend Bonita, then on to Las Cruces, NM, to stay with Rob & Eleni, Philadelphia friends renting a snowbird getaway

If I’m enjoying the ride, keep going, via Adventure Cycling’s Southern Tier route, to New Orleans, then maybe Florida

Ride back to Durham in March/April via the East Coast Greenway? …But I’m getting ahead of myself

A Note About This Blog:

Before I left, some friends asked whether I would make a blog of the trip, or a video or audio documentary. I had no intention of doing so. I’ve long believed that if you concentrate too much on documenting your life, it keeps you from actually experiencing it as it happens. I said I would send postcards from the road, and that would be it.

This absolutist stance evaporated as soon as I set out. The first day, I found myself sending photos of interesting things I was seeing in the greater LA area to Hannah and her family. Soon I found I wanted to stay in touch with all my friends. I didn’t bring my laptop, but I had my phone, so when several friends started asking how things were going, I began recounting each day’s adventures in nightly emails. Those emails became the log of my trip, which is the raw material for this blog.

Part of my low-documentation ethos survived, in that I didn’t take as many photos as I would have if I’d had it in mind to create this blog. I didn’t photograph the people I met, or get “establishing shots” of the places I went. And early on, I learned that vistas that were stunning to my eye were rendered puny and dull by the iPhone. So the photos that follow are kind of a random smattering of what looked interesting to me at the time, or what I thought might interest a friend.

Pre-ride: Base Camp

Setting up the tent, for the first time, in the dark (photo by Hannah)

Okay, so I admit I’m not big on planning. I prefer to do things half-assed and last-minute. After my roommate Steven advised me on camping gear, I didn’t order it early enough to get it to Durham before I left for LA. So an extremely light tent (2 lbs.), sleeping bag (2 1/2 lbs.), and pad (1 lb.) were shipped to Hannah in Glendale.

I definitely wanted to test them before my trip. Turns out my nephew was having a small birthday sleepover the night I arrived, so they didn’t have a bed for me. Perfect!

Hannah and I looked online and found a campsite called Millard Trail Camp in Angeles National Forest, just 20 minutes from her house (by car). My flight arrived in the late afternoon, so by the time she drove me there, everything was pitch black (and deserted—due to COVID?). She held a flashlight while I puzzled out the tent.

I’m not used to camping, and in some ways I’m big on hygiene, so I’d asked her if I could borrow a small bedsheet to line the sleeping bag. That was all I needed to stay comfortable when I bedded down under 50º skies. As the temperature dipped to 40º, though, it got a little chilly. So, the next day, it was off to REI for a warmer silk liner, as well as wool long johns. With these, my wool socks, and a sleeping bag rated for 25º, I figured a cold night in the Southwest desert would be fairly comfortable. Or at least survivable.

Pre-Ride: Test Spin

The ride, it turned out, was a breeze! Jacopo’s handiwork made my bike roll completely smoothly, better than it ever had before; fully loaded, it felt like your grandfather’s Oldsmobile, a two-wheeled locomotive of majestic heft and inertia.

And I was delighted to discover that biking in LA is an exquisite pleasure (at least in the Glendale/North Hollywood area). Google’s route put me on small neighborhood through streets, briefly on a bike path along the LA River, and a few miles in an expansive bike lane on Riverside Drive. Heavenly.

Another bit of planning I’d skipped before leaving Durham was a test ride with fully loaded panniers. I’d bought them just a week before my flight, and in that final week at home I was too busy (and, frankly, lazy) to test them out. Besides, I used to be a pedicab driver, and the bike alone, without passengers, weighed 200 lbs. How hard could it be to lug 50 lbs. of gear?

I finally found out just a couple of days before I started my trip, when I pedaled eight miles to visit my friend Neil in North Hollywood. I packed my front and rear panniers with most of what I would take on my trip, and lit out on a sunny SoCal afternoon.

Day 1: Roll Out!

Glendale to San Bernardino, 67 miles

I ended up spending a week in Glendale. While Mike worked from home and Linus attended virtual middle school, Hannah helped me get my gear together, with trips to three bike shops, Best Buy, and REI (twice). Finally, on December 11, it was time to head out.

Five minutes to liftoff (photo by Hannah)

My first day’s destination was a Motel 6 in San Bernardino, halfway to my friend Richie’s house in Palm Springs. The 67-mile distance is just a bit farther than the weekly training rides I’d taken to and from La Farm bakery in Cary, NC. (Pastries are a great motivator!) Those rides had built up the strength in my legs and heart till they started to feel no more taxing than a walk around the block. But how would it feel with the full weight of my gear?

Turns out, I didn’t feel a thing. That might partly be due to my new philosophy of biking: When I first started biking as an adult, I was in my 30s and living in Brooklyn. By reflex, I would go all-out, full-speed, everywhere I went. (It’s not just that I was young; I think it’s also a New York thing.) Now, with 50-year-old joints that are off warranty, and living in the laid-back South, I’m just as happy to pedal lightly, expending little effort and enjoying the roll.

And, that first day—what a roll! I traversed the San Gabriel Valley and its eastern environs: Pasadena, Arcadia, Azusa, Glendora, San Dimas, Claremont, Rancho Cucamonga, Fontana. I rode through old neighborhoods, new subdivisions, downtowns, apartment complexes. Briefly but memorably, a stretch of open desert on the San Gabriel River Trail bikeway.

The highlight of the day was the Pacific Electric Bike Trail, 21 miles of peaceful, stress-free sail. With no traffic to worry about, I was free to gaze promiscuously, taking in myriad interesting details and the whole breadth of the metropolis. I was feeling a kind of euphoria.

The Motel 6 at the end of my journey lay in an ugly industrial zone in the shadow of the roaring Interstate 10. Though I arrived well after dark, I wasn’t at all tired. I was confident now that my legs could carry me virtually any distance.

One interaction lingers in my memory: Five miles into the trip, I started up a big, steep hill in Pasadena, shifting to the lowest gear and slowing to walking speed. I noticed a retirement-age woman walking on the sidewalk next to me, looking quizzical, like she was trying to figure out what the big yellow bags on my front and back wheels could possibly be for.

“Getting a little exercise?” she asked.

“Nope,” I replied. “Going to Florida.”

Day 2: Friends in Low Places

San Bernardino to Palm Springs, 58 miles

On Day 2, I emerged from the Motel 6 into a hazy 50° morning. The ride began in sleepy suburban neighborhoods, then turned onto a hilly country road that wound through orange groves and horse ranches. It was picturesque, but it had no shoulder, and passing cars and trucks went very fast, so it was not terribly pleasant to bike on. I also had to fight through a 2,000-foot elevation gain. But the calm beauty of the bucolic countryside, so close to LA, made up for the hardship.

As I wended my way to the hill towns of Beaumont and Banning, gloomy clouds and fog rolled in, and the day turned chilly, the temperature dropping to 46°. Cold and weary, I was lucky to find a pho place with vegetable broth. It was a much-needed boost.

Fortuitous drainage tunnel under I-10

After lunch, twice I had to deviate from Google’s biking directions. The first time was at the foot of a restricted-access road on a small Indian reservation, where a guard in a kiosk refused me passage. “You’ll slow traffic,” he said, as I watched a grand total of one car go by while we talked. He directed me to nearby railroad tracks, alongside of which ran a primitive dirt road Google wasn’t hip to. It was rough going, but kind of fun. Later, Google would have had me bike on the teeming I-10 freeway—uh, no. Again, I found a dirt road solution, a service road for windmill maintenance. It was so sandy I had to walk for stretches. I exited by hopping a barbed-wire fence and ducking under I-10 via a small drainage tunnel.

Most amazingly, the prevailing winds that drive fields of windmills in the mountain pass were so strong, they basically blew me to Palm Springs! Some credit is due to the slope of the road, which was more or less continuously downhill: Palm Springs is not much higher than sea level, 2,500 feet lower than the highest point I reached on my bike. But it was also the crazy-strong wind that caught my panniers as if they were sails, quickly accelerating me so that sometimes I had to squeeze the brakes. I didn’t pedal for two hours!

My destination was the winter home of my friend Richie from college, and his husband David. The long day’s journey was capped by a delicious pasta-and-mushroom dinner Richie made. They also let me do a tiny load of laundry. Then I repaired to the most charming tiny guest house I’ve ever seen in my life. What tremendous hosts!

David (L) and Richie—I forgot to take their picture, so they sent this one to me

The cutest one-room guest house ever

Day 3: Camping with the Uncouth

Palm Springs to Slab City, 81 miles

In the morning, Richie had a wonderful breakfast waiting for me, the perfect fuel for a long ride. In fact, Day 3’s 81-mile run would be the farthest I’d ever ridden a bike. The good news: I was glad to discover that it wasn’t difficult. After eight hours in the saddle, including a long spell on a picturesque, lonely highway along the Salton Sea, I still had plenty left in the tank. The bad news: The last couple of hours, I rode in pitch-black darkness. Those who don’t cycle for transportation are often surprised to learn that biking at night in cities is no problem at all; in fact, it’s quite pleasant. But subtract the street lights, and it’s stressful. You can’t see anything outside the cone of your headlamp, which induces a kind of hypnotizing tunnel vision, making it hard to keep your eyes peeled for hazards. It’s an exercise in grim endurance.

I had settled on Slab City as my third stop thanks to a listing on warmshowers.org, an online network for touring bicyclists and potential hosts. My host, Dan, said in his profile that he operates a free food kitchen/dive bar at a skate park. So far so good, I thought.

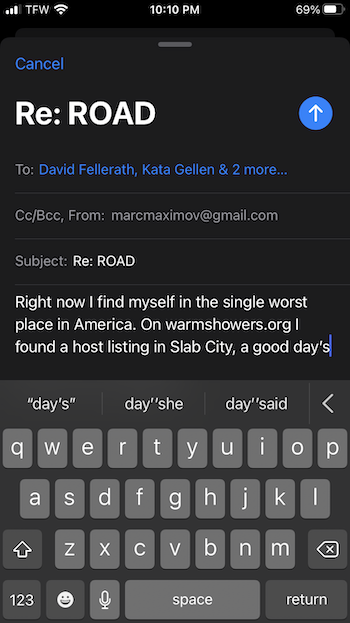

Emailing about my night with the vulgarians

I didn’t know much about Slab City. I’d heard it’s some sort of libertarian/anarchist fantasyland, where you can stake out an unclaimed patch of dirt, claim it for yourself, and homestead. Rolling into town, its feral nature quickly became apparent, as I was twice chased by big, angry dogs (I later learned that off-leash dogs are the norm). And there are no street lights, so I had to rely on my phone’s GPS to find Slab City Skate Park in the dark.

I texted Dan, and he came out to greet me. A kind and gracious thirty-something, he invited me into the large tent that houses the dive bar, and gave me a free soda. (I just said no to Budweiser and Natty Ice). We chatted a bit about long-distance biking, but the bar’s blaring classic rock drowned our conversation, and the resulting shouting was making me tired (I know, I know, it’s not that the music’s too loud, it’s that I’m too old). To top it off, the close quarters, with a dozen or so patrons huddled around a tiny bar, shouting in each other’s ears, seemed like a COVID risk. I told Dan I’d love to chat later, but now I was turning in for the night. I went to set up my tent, trying to find a spot away from the music but not too far out in the desert.

Once in my tent, I was bombarded for hours by the ravings of drunks who stumbled to and from the bar and hung out on nearby outdoor couches. I really should have moved farther away, but moving the tent is a hassle, so I stayed put. As a result, I was exposed to a class of drunken brouhaha so vile, it was genuinely new to me. It was still too early to sleep, so I wrote an email to several friends describing the experience (see screenshot at right).

I can only suppose the free food and beer (furnished by whom?) had attracted a critical mass of mean, angry drunks who were core to the scene. The top-volume yelling was so nasty, it bordered on comedy: “Fuck you!” “No, fuck you!” “You cunt!” “Don’t stick your finger up my asshole! I was passed out!” I don’t think of myself as overly polite, but this was the single most uncouth crowd I’ve ever witnessed. The awfulness reached a crescendo when several free-roaming dogs that had barked at me as I set up my tent started full-bore dogfighting each other, which brought out a round of vituperative, accusatory shouting from their owners.

“I’m too old for this,” I typed to my friends.

Day 4: Slab City and a Short Ride

Slab City to Brawley, 23 miles

By some miracle, the bar closed before midnight, and the partying (if you can call it that) quieted down. In the morning, my mild-mannered host was nowhere to be seen, and I didn’t really want to socialize with the skate-park crowd, even if the middle-aged oddballs quietly chatting on outdoor couches maybe weren’t the same people who’d so charmed me the night before. Since today’s ride would only be 23 miles, I had plenty of time to explore Slab City.

Morning at Salvation Mountain

What a strange place! I’m certain there’s nowhere in America like it. I didn’t end up talking to anyone there—it would’ve really helped to have a Virgil—but from the looks of things, the denizens are a mixed bag of artists, burnouts, misfits, “patriots,” hippies, and off-the-grid homesteaders. It looked post-apocalyptic, a world built from civilization’s junk.

No trip to Slab City would be complete without a stop at Salvation Mountain, which manages to be both homespun and very impressive. (If you’ve seen the movie Into the Wild, you’ll recognize it in a key scene.) Amid Slab City’s chaos, its message of love and kindness felt refreshingly upbeat.

After a short ride to Brawley, I holed up in a hotel room to rest up for the next day. I’d gone 230 miles in four days without feeling any strain, but tomorrow’s ride, 89 miles from Brawley to Blythe, would be the true test. Adventure Cycling’s Southern Tier map says, for those heading east, “Stock up on food and water in Brawley; services are very limited until Palo Verde.” Which is 68 miles away! This ride would be my first major departure from civilization. Of course, bike touring isn’t wilderness trekking, and if something goes seriously wrong, you can just wave down a passing motorist. But I wanted to make it to Blythe (or at least Palo Verde) under my own power. I packed two days’ worth of food, and hoped to find extra water in Glamis, two hours’ ride to the east. I’d have food, water, a tent, a sleeping bag, and warm clothes. I’d make it, no problem. Right?

I had trouble sleeping that night.

Interlude: The Things I Carried

With hours to kill in my Brawley hotel, I decided to do an inventory of my possessions. I’ve noticed that every cross-country biking blog includes an inventory, and now I know why: You have to pare down to the essentials, and it’s fun to see each person’s idea of what that is. Since this was my first excursion, my choices were based on a combination of advice from fellow travelers and my own best guesses. I planned to re-evaluate when I got to Tucson. But this is what I started with.

The whole enchilada (minus bike, panniers, and food)

Camping Stuff

Tent

Sleeping bag

Pad

Bedsheet sleeping bag liner

Silk/cotton thermal sleeping bag liner

Inflatable pillow

Pillow stuff sack

Bike Stuff

2 water bottles

Pump

4 spokes

4 tubes

2 tire levers

Chain lube

Brake pads

Chain links

Presta/Schrader valve adapter

3 patch kits

Multi tool

Foldable tire

Front & rear lights

Combo cable lock

Bag to put bike stuff in

Clothes

Shoes

Flip-flops

Jeans with belt

3 shirts

2 pairs shorts

4 pairs underwear

4 pairs socks

Warm Clothes

Nylon windbreaker pants

Wool long underwear (top and bottom)

Nylon windbreaker jacket

Sweatshirt

Scarf

Wool socks

Heavy coat

Hat

Gloves

Miscellaneous

Portable battery cell phone charger

Shure MV88 stereo microphone (for use with cell phone)

4 AAA batteries

Magazine

Reading glasses

Postcards

Mechanical pencils

COVID face mask

Cell phone with sewn case

4 AA batteries

2 USB power cubes

Cell phone charging cable

Apple Watch charging cable

Tweezers

Dental night guard

Fingernail clippers

Earplugs

Deodorant

Toothbrush & toothpaste

Small bar soap

Plastic knife, fork, and spoon

Napkins

Sanitizing wipes

Mini flashlight

ADDED AFTER THIS PHOTO:

Sunscreen! (What was I thinking?)

Baby wipes

Skin lotion

Zip ties

Pen

Day 5: The Test

Brawley to Blythe, 89 miles 97 miles

I wanted to get to Blythe before sundown, so I woke up early and saw 5 am for the first time in a long time. I was checked out of the hotel and on the road a little after 6, well before the sunrise. Google estimated it would take 7 hours on a bike, and I bet I could do it in 6 with no gear. Fully loaded, I knew it would take 8 or more likely 9 hours.

Dunes in Glamis

I arrived at the teeny-tiny town of Glamis at quarter to 9. I was making good time. I stopped at the single store in town, gulped down a small bottled water, and threw a liter in my pack. It was 41 miles to Palo Verde, where I planned to camp if I couldn’t make it all the way to Blythe. I was ready for anything.

With perfect weather and a generous shoulder on Route 78, I visualized a triumphant 2 p.m. arrival in Blythe. 89 miles would go down easy, and I’d have plenty of time to relax. But the desert had different plans for me...

As Route 78 turned north, the generous shoulder got less generous, then disappeared. The wind started to pick up. By 10:30 a.m. it was a howling gale, blowing directly in my face. The “easy does it” pace that had served me so well wasn’t working; I had to pedal hard to move slowly.

Also, the terrain changed to a series of roller-coaster climbs and drops. At least a dozen times, I had to dismount and walk my bike on the upslope, and in the face of the wind, I had to actively pedal to pick up speed on the downslope.

Cool monument to a pre-Columbian trail that Native Americans used to travel from the Colorado River to Lake Coachella

I looked at mile markers and saw I was going about 5 miles an hour, with 50 miles to go till Blythe. Would it be better to stop and wait, hoping the wind would die down? Try to set up camp and see if conditions would be better tomorrow? I gritted my teeth and pressed on.

A guy in the passenger seat of a passing car saw me struggling, leaned out the window, raised a fist, and shouted, “Keep on cruising, man!” That buoyed my spirits. So did my first sighting of another touring cyclist, when a man on a pannier-laden bike going the other direction pedaled into view. “Having fun?” he yelled across the road, grinning. “Maybe if the wind were at my back!” I shouted back, laughing.

I felt foolish for not having stopped to say hello—what were the odds of running into another bicyclist out here, in the middle of nowhere?—so when I saw another pack-laden cyclist coming down the road a few minutes later, I crossed to her side to say hello. Her name was Kera, and the man I’d passed minutes earlier was her boyfriend Bill. She said they were headed to San Diego... from Bar Harbor, Maine, where they’d hopped on touring bikes in August right after completing the Appalachian Trail. Wow! (I Google-searched them and found this article from their hometown newspaper. Are they too young to be my role models?)

The wind was so relentless we had to shout, and I wanted to get to Blythe before dark, so our chat was brief. My struggle with the insane wind, on the other hand, lasted about three more hours. Finally, it weakened enough for me to make decent headway. Such a relief! Now it looked like I’d get to Blythe by 4:30, with plenty of light in the sky.

An unplanned detour leads to the Colorado River

Nearing the town of Palo Verde, I took Kera’s recommendation and left Route 78 to take dirt roads surrounding Oxbow, the campsite they’d stayed at. I crossed a bridge over the Colorado River, and suddenly I was in Arizona!

The dirt roads were rough going—surely they were easier for Bill and Kera, whose tires are twice as wide as mine—but I couldn’t stop gawking at the beautiful landscapes, which neither my iPhone’s camera nor my non-photographer’s eye can do justice. And, though this route was slightly out of the way, the curving dirt road I was on would still take me to Blythe.

Or... not. It turned out the bridge I would’ve used to cross back to California was closed for maintenance. I had to backtrack all the way I’d come on the rugged dirt road. I was a half-hour in, which meant I had lost a whole hour and would arrive in Blythe around 5:30 in complete darkness.

After the backtrack—and I admit, the landscape was so beautiful, I almost didn’t mind the repeat viewing from the opposite angle—I pedaled hard for the last hour and finally arrived in Blythe, where I was welcomed by a series of mysterious fires blowing across the road. As I learned later, it was farm fields that had been set ablaze—which I know is a common agricultural practice, but this was within the city limits, smoke blowing directly into neighborhoods, which seemed wrong. In any case, I held my breath as I passed through each noxious, blinding cloud. The only consequence was that, standing in the lobby of the hotel I would check into, I noticed I smelled strongly of smoke (I imagined explaining to the desk clerk: “No, really, I want a non-smoking room!”)

I was cold, hungry (problem solved by a great burrito from a locally-owned Mexican place), and in need of a day of rest. I’d just pedaled 11 ½ hours straight, with only a few brief pauses to buy water, apply and reapply sun block, and wolf down snacks. I traced my route online and found that the dirt-road backtracking added to a total trip of at least 97 miles. It was good to know my legs have that in them, even in the teeth of insane headwinds!

Day 6: Go Rest, Old Man

She apologized and said they wouldn’t serve me, so I started to leave.

Then, an idea: I approached the SUV behind me and asked, “Excuse me, would you mind ordering for me? I can give you cash.”

Two men were in the expensive-looking vehicle. In a (South Asian) Indian accent, the passenger said, “Okay, what do you want?”

“An Epic Avocado burrito,” I said. They ordered it. I started to explain that I had ridden my bike into town from LA, but he rolled his window up and kept it up. I walked alongside the vehicle as they advanced in line.

They got the food and handed me the burrito. I thanked them and held out a $10 bill.

“It’s okay,” the passenger said.

“I have plenty of money,” I told him. “I just don’t have a car.”

“Don’t worry about it. Enjoy your dinner,” he said as they drove off.

I think they thought I was homeless.

After the prior day’s odyssey, I needed a day off. I wrote postcards, caught up on emails, and got what enjoyment I could out of Blythe, which wasn’t much. There’s a historical museum I might’ve checked out in non-COVID times, and if I hadn’t taken a vow of stasis, 14 miles out of town there are huge pictographs made by ancient people, apparently best seen from the air.

One funny story I’ll relate: For dinner, I tried to go back to the locally-owned, cheap Mexican place I’d hit up the night before, but they were closed, so I defaulted to the Del Taco across the street.

I was disgruntled to find that they were only open for drive-through. My bike was back at the hotel, so I was on foot. I thought I’d take a chance and stand in line behind the cars. Sure enough, they would not let me order. An employee popped out of the rear door to tell me, “Sir, this is drive-through only.”

“You’re telling me I need to bring a car to order food here?” I asked. I knew the answer, and I know this employee doesn’t make policy, but I just had to register my annoyance.

Day 7: A Cute Chapel and a Curious Chat

Blythe, CA to Salome, AZ, 66 miles

Well-rested and free-breakfasted, I left the Econolodge, rode east, and soon crossed the Colorado River (again) via a pedestrian walkway. Now it was official: For the first time, I had ridden my bike from one state to another, and I was back home in Arizona!

The 65-mile ride to Salome would include 20 miles on Interstate 10. Normally it’s illegal to bike on interstates, but Adventure Cycling says an exception is made here because there’s no other way to go. Merging from the on-ramp, I immediately thought of my late mom, who drove 18-wheelers for a few years in the 1980s. I’m sure she’d passed through this stretch of I-10 many times. I teared up at her memory. And, this might sound stupid (or simply human), but I credited her spirit with opening up big spaces for me each time I had to cross traffic lanes at on- and off-ramps. Otherwise, travel on the interstate was uneventful. Traffic was much lighter than in the LA area, and the shoulder, as wide as the travel lanes, was my own private bike lane.

I set my sights on Salome because a big park named Centennial looked like a good place to camp, with or without official sanction. After three days in hotels, I decided to have another go at the tent, to stop hemorrhaging money, and to test my gear and my toughness: The projected low would be in the 30s.

On the way to the park, I spotted a sign for a teeny-tiny chapel.

I went in and signed the guest book. A sign invited me to fill out a “prayer form” on a little slip of paper and drop it in a box. Each day’s prayers, it was promised, would be personally prayed the next morning by the chapel’s custodians. I requested prayers for my safe return home, and for the health of my father and stepmother back in Tucson.

I got to the park just before dark. I was prepared to look for an out-of-the-way patch of desert to set up a contraband camp, but I decided first to check out the official campground. I saw a sign and read the rates: $16/night for RVs, $8 for tents. Just then, the “camp host” walked up behind me and asked if I had any questions. So began one of the strangest conversations of my life.

The host was a man named John, originally from Indiana, with a cheerful and humble manner. Within five minutes of introducing himself, after I’d mentioned I’m from North Carolina, he began to relate his experience at a music festival in the Blue Ridge Mountains in the 1990s. Walking on a trail at the edge of the festival, he saw a mysterious glow—foxfire, he later learned—and followed it into the woods.

The foxfire split in two, appearing now as a glowing pair of eyes, and seemed to guide him along, imparting a mysterious message. It induced him to cross a river that he shouldn’t have been able to cross on foot. And then... The story was interrupted by the appearance of John’s cat, Midnight, with whom he has a “shamanistic relationship.”

Midnight the cat, who doesn’t like to pose for pictures

I mentioned I love cats; John said he’s amazed at the power of the inter-species bond between cat and human. For a moment I thought: If my life had turned out just a little differently, would I be living in a van at a campground in Salome?

Darkness was falling. John pointed to blinking lights in the night sky. “Those are planes,” I said. “No,” he said. “Drones.” He told me they blink in patterns that encode messages, and that the Air Force is trying to put his theories of physics to bad ends.

Okay, so… John is crazy. A layman could diagnose paranoid schizophrenia. But I found him fascinating. As kooky as he was, he was also totally earnest and genial, and—here’s the interesting part—he has a very deep and detailed grasp of astronomy, cosmology, and particle physics.

We discussed—I should say, he discussed, while I asked and encouraged—general relativity, black holes, space and time. I admired his curiosity, and his dedicated study of science and other explanations of reality. As he went on, though, I was disappointed to learn that he subscribes to some of the more ridiculous unscientific conspiracy theories: For instance, he’s been persuaded that the earth is flat, and that the moon landings were faked. I gently tried to poke holes in these theories, but he’d bring up some obscure point that supposedly debunks the mainstream view (“Russian scientists proved that the human eye can’t withstand the radiation that exists above the stratosphere,” and such). In any case, he wasn’t really open to receiving information, only dispensing it.

His one-way communication style, and his belief in dumb theories, didn’t make him any less fascinating to talk to. Perhaps (if I can presume to diagnose) his paranoid schizophrenia makes him especially inward-facing, and susceptible to distrusting conventional reality. In any case, living alone in a van in the middle of nowhere, he clearly has few people to talk to. He told me he has a YouTube channel where he discusses his theories, having found there a community of like-minded seekers with whom he exchanges texts and emails. He said he’d give me the link to his channel.

It was getting dark and very cold. I told him we could continue in the morning, but I needed to set up camp.

In my tent, I enjoyed a dinner of peanut butter and Nutella sandwiches. (Note: Nutella is not spreadable at 40°.) I was very curious to know if my gear could keep me warm with temperatures in the 30s. I put on my long underwear, inserted both liners—cotton and silk—into the sleeping bag, and lay down to sleep at 9 pm. All was well… except my feet were cold. I put cotton socks over the wool socks. Still cold. I zipped up my heavy winter coat and put it around my feet at the bottom of the sleeping bag. My feet were now encased in a 7-layer insulation burrito: wool socks, cotton socks, heavy coat, silk sleeping bag liner, cotton liner, sleeping bag, pad, tent. Friends, they were still cold!

The temperature was only going to keep dropping. I started to fret. Is this how people get frostbite and lose toes? Or is it nothing to worry about? For me, having cold feet was a new experience, but was it no more serious than the many times girlfriends told me their feet were ice cubes as we lay in bed in 68° rooms? (To be fair, their feet were ice cubes! Fortunately, I’m a human furnace, and it was well within my capacity to warm them up.)

For each foot, I reached down, took the socks off, and rubbed it vigorously to get blood flowing. After about 10 minutes of this, they started to warm—my furnace was lit! Soon my toes felt positively toasty. But the temperature continued to fall. I found I was able to just barely keep my furnace running by ducking my head (wearing a knit cap) entirely under the lip of my extra-long sleeping bag, stealing two hours of sleep at a time.

Day 8: What a Long, Straight Trip

Salome to Wickenburg, 52 miles

I woke at 7 with the dawn. I’d survived! And just barely stayed on the right side of toasty vs. chilly.

I went to pack up my stuff. Just as I was finishing, John emerged from his van. He said that just before dawn, the chill air had dipped below freezing: He pointed to the aboveground pipe at his camping spot, where the water was frozen solid. He asked how I’d slept. I was proud to say my first night outdoors in freezing temperatures was a success.

One of the many roadside memorials I passed on my way to Wickenburg. I photographed eight of them on my trip, each time pausing for a moment of silence for the deceased.

We talked for maybe 20 minutes more, and then I bid him adieu. Much as I’d genuinely enjoyed our interaction, his style of 95% talking and 5% (reluctant) listening means it’s probably best he’s a loner. He asked for my phone number. I gave him my email address instead. He hasn’t emailed, which vexes me—I really wanted to thank him for his hospitality, and see his YouTube channel. Maybe he copied down my email address wrong?

The ride to Wickenburg was, uh, consistent. This might’ve been the first truly dull portion of my trip. With nothing much to see and 52 miles of long, straight, mostly featureless roads, I spent a lot of time cogitating. I pondered my brief but deep interaction with John. There’s something poignant about his lonely search for meaning, interpreting messages in blinking lights at night, and using the internet to find friends. With his intense curiosity and fine (if confused) mind, in a parallel universe, could he have been, say, a physicist or astronomer? No; scientists speak in math, whereas John prefers to play with concepts. In any case, by withdrawing to a hermit-like existence, is he depriving the world of some positive use of his gifts?

The miles ticked by as I mulled the puzzle of John, and thought about my own life.

Day 9: God Bowls a Strike

Wickenburg to Scottsdale, 63 miles Horse trailers and tourniquets and helicopters, oh my!

When checking into the Wickenburg Best Western hotel the day before, I had been surprised to find there were few vacancies. Why, during COVID season? The front desk clerk said it’s the rodeos: Wickenburg is one of the rodeo capitals of the US, and they have events from November through April. Huh. Who knew?

I breakfasted and got on the road sometime after 9 am. My cousins Terie and Mark in the Phoenix suburb of Scottsdale had graciously agreed to put me up for the night. The next day, I’d make it halfway to Tucson, stopping in Coolidge, where I had arranged to camp at the home of a friendly Warmshowers host. The day after that, at last: A triumphant, two-wheeled, self-powered arrival in my hometown.

Moseying down AZ Highway 60, I saw the ways in which Wickenburg is a Phoenix exurb—it’s an hour away from downtown by car, if traffic doesn’t clog—and its more rural qualities. It’s definitely horse country, with lots of signs for boarding, rentals, dude ranches, and properties with stables on site. I turned off onto AZ Highway 74, which begins with a straight shot of about 15 miles. After that, it would open up into potentially more scenic country, and then I would navigate suburban Phoenix to my cousin’s house. But for now, I was stuck with another uneventful ride like I’d had the day before.

Except, it wasn’t. At around 10:15 am, after looking down to check my rear tire pressure, I looked up to see a car tire barreling toward me, probably doing something like 60 mph. There was no time to dodge it. It was going to be a direct hit. “I guess we’re doing this,” I thought.

A split-second later I was in the air, then on the asphalt. I tried to get up, only to find that my right femur was bent at a grotesque 90º angle. Instinctively, I realigned my upper leg, then lay on my side in the wide shoulder I’d been riding in. I could feel warm blood soaking my shorts and forming a pool on the blacktop. A man driving an SUV westbound was the first to stop. “Are you okay?” he asked. “No,” I said. “I have a broken femur!” He saw the blood and freaked out a little bit. He dialed 911.

Another man pulled over to help, and the two of them discussed making a tourniquet. Just then, a third good samaritan pulled over, jumped out of her pickup and kneeled over me. “I’m a nurse,” she said. She asked how I was doing. “I have a broken femur,” I gasped. She called to her husband: “Get my kit!” She just happened to be traveling with a tourniquet.

A selfie shortly after surgery (folks had compassionately made sure my wallet and phone traveled with me throughout my ordeal)

Time seemed to crawl, and I remember everything that happened—by which I mean to say, I never passed out, so I remember most of the ensuing events, though I couldn’t give a perfectly detailed blow-by-blow. I asked the nurse’s name. Heather, she said, as she applied the tourniquet and injected a painkiller.

Fortunately, the purple bag that held my wallet and phone had landed not far from me, and my phone was cracked but serviceable. Lying on the pavement, my bleeding stanched by Heather’s tourniquet, and with a right thumb that was jammed into my hand and sticking out at an awful angle (I had to pop it back into place three times to get it to stay), I used my watch to dial my father and let him know what was happening. He stayed on the line while activity buzzed around me.

The EMTs arrived. I managed to get the name of Cory, whom I will hope to track down for a Christmas gift. And if anyone has an idea of how to go about finding the nurse named Heather, who saved my life, please share it!

There was discussion of landing a helicopter on the highway to speed my trip to a Phoenix hospital, about 30 miles by air from where I lay. It was determined that the helicopter would be slightly delayed, so there was time to first drive me to what I now think was a fire station in nearby Morristown. From there, I was loaded into the chopper (my father lost my phone signal after we launched skyward). I could hear the blades whirring, but I had a neck brace on, so all I could see was the cabin roof and the face of the medic watching over me.

The flight was over quickly, and I was wheeled into a hospital emergency room, where I was run repeatedly through some sort of scanning machine. I was conscious and responsive to questions, but at some point in the helicopter ride, I had begun to undergo what I can only describe as an out-of-body experience. Whether it was the drugs (I think they’d injected me with fentanyl and ketamine?), the shock, the blood loss… I don’t know. I felt like I was experiencing another plane of existence. It was neither calming nor frightening, rather intensely fascinating. It’s impossible to put into words, and now I only remember the experience dimly. In any case, while I moved through that realm, I was kept in this one by the need to answer some questions.

In the surgery prep room, a surgeon explained that he would insert metal rods into my femur and tibia. He said he might also have to work on my knee. I requested he leave the joint as-is to the extent possible. (Good call? Bad call? Yikes! We’ll see how this turns out.) Then a police officer came to take my statement. I told him what I heard while lying on the highway: One of the people standing over me—I believe it was the first good samaritan, the man who made the 911 call—had said he watched a wheel detach from a horse trailer and come barreling toward me. I told the officer I wished I’d had time to dodge it.

Silver Linings

I dearly wish that the fateful horse-trailer wheel, which I’ve taken to calling the Wheel of Misfortune, had turned just a few feet to the left or right before it so rudely occupied my longitude. On the other hand, the past two weeks have not been altogether negative. The flood of well-wishes from friends and family has been incredibly cheering.

Some rehab staffers made Christmas blankets for all the patients. It’s cozy and cheerful and I get to take it home!

Each day since my accident has been filled with emails, texts, and phone calls from the people I love. The night of my surgery, my cousin Terie dropped off a cell-phone charger and extension cord at the hospital. In the following week, my father and sister mailed me other things I needed. And some friends organized meal deliveries to the hospital, which was touching and delightful. I am truly blessed!

I’m also exceedinlgy fortunate to have health insurance. I had none through age 44, and when I left my full-time job with benefits in 2018 and started freelancing, Obamacare was there for me. There’s no way I could have afforded health insurance without it. I’m grateful that Republican lawmakers have so far been unable to kill it.

As I type this, it’s New Year’s Eve, and I’m perched on the second floor of a rehabilitation center in a northwest Phoenix suburb. The therapists, nurses, and doctors here have been absolutely wonderful: I think the healthcare field tends to draw the best kind of person. Physical therapy has introduced me to new worlds of pain, beyond anything I’d imagined; I trust that adversity makes us stronger, and, if we’re lucky, more understanding.

I hope to fulfill the more optimistic projections of my recovery: Six months to walking/biking/running, and a year to a full return to the pre-crash me of two weeks ago. Wish me luck! If all goes well, I will get back on the road and continue my journey in December 2021.

The San Gabriel River Trail in greater Los Angeles

Near the Salton Sea

At Slab City Skate Park

Aspen grove on agricultural land near Cibola National Wildlife Refuge

Another way to get around on wheels

Seeing the dawn break from my hospital bed at Banner Rehabilitation Hospital West

Updates

December 30, 2020: Arizona Highway Patrol has notified me they believe they have found the horse trailer the wheel came off of. They are planning to prosecute a criminal hit-and-run case. I dearly want to know whether my beloved bike is salvageable, but they will not return it to me for some time because it is evidence.

Photo by Hannah

January 5, 2021: Yesterday Hannah arrived from LA to help me with everything (what a sister!). We’re staying at an Airbnb. Today, we retrieved my panniers from the Arizona Department of Public Safety. The clerk allowed us a peek at my bicycle—he didn’t have clearance to do so, so we weren’t allowed to take photos. It is totaled. The front wheel is a frightening mass of twisted wires, and the front of the frame is bent at a severe angle. The clerk said he was surprised that the person riding it is still alive.

January 12, 2021: While Hannah and I were driving from Phoenix to LA, AZ Highway Patrol contacted my lawyer with a few more details about the case. It seems the horse trailer belongs to a woman involved in rodeo barrel-racing. She’s denying that the wheel is hers, while law enforcement is engaging a forensic expert to prove that it is. As early as next week, the police may give my lawyer access to an accident report, and he can then try to find out whether they had insurance.

My right leg doesn’t seem to have gotten better in the past couple of weeks, but physical therapists tell me I just need to be patient. It’s a long road ahead!

March 6, 2021: I flew back to Durham on February 2nd to continue my rehabilitation at home. The last two months have seen considerable progress, for my leg and my legal case. I passed a major milestone three weeks ago: I can walk without crutches (hurrah!). Only for short periods, though: I stagger through the house in a jerky, wall-bracing limp, only occasionally applying the steady effort needed to achieve a proper (slow-motion) stride. For trips outside the house, I need crutches.

My physical therapist, a reassuringly knowledgeable North Dakotan named Ger (like in Gerhardt), says the walking shows great progress, but my main task is to bend my knee. At our last session I achieved 120º, which means I’m on a good pace: I’m adding about a degree a day. My home bending sessions, which I do 3–5 times daily, are grueling, but less so each week.

On the legal front, a lot has happened! On February 12, Arizona’s Department of Public Safety finally released the police report to my lawyer. It’s eleven pages of all-caps testimony from a couple of different officers, along with some filled-out forms and a crash diagram (left). It’s gripping reading: I call it CSI: Morristown (after the tiny census-designated place near the crash site, which I think is where the ambulance took me to get picked up by a helicopter).

“Vehicle 1” (part of it, anyway) meets “Vehicle 2” (me)

The report explains that after highway patrol had locked down the crash site, with police cars diverting traffic on both sides of me, and picked up the rogue wheel as evidence, one officer went driving around Wickenburg in search of a horse trailer missing a wheel. He searched fruitlessly for two and a half hours—apparently, law enforcement takes hit-and-run very seriously!

At approximately 3:20 pm (1520 hours in police-speak), an hour and a half after the officer had stopped looking, he found the trailer! It was plainly visible from the road, parked in front of a closed diesel repair shop. The officer waited three hours until a truck pulled up to the trailer. A woman got out and confirmed the trailer was hers. She said it had lost a wheel on Highway 74, near where I was struck.

What happened to the wheel? he asked. She said she had found it and put it in the trailer. Could he see it? She opened the trailer and showed him a wheel that “HAD DIRT IN THE TREAD OF THE TIRE. VISIBLE SPIDER WEBS WITH DUST AND VEGETATION HUNG FROM THE SUPPORT ARMS OF THE HUBCAP. THE TIRE DID NOT APPEAR USED NOR INVOLVED IN A COLLISION AS THE TIRE FOUND FROM THE COLLISION SCENE.” He read her her Miranda rights, and seized the trailer as evidence.

I remember lying on the asphalt while the first good samaritan to stop and help me talked to the 911 operator. He told them he thought he saw that the trailer had pulled over up ahead. If that’s so, why didn’t the driver come get their wheel, and check up on me? Why did she later make up a fake story for the police? What could she have been thinking? I am morbidly curious to know the answers to these questions. As it is, her poor judgment means she’s facing a felony hit-and-run charge. At a minimum, she’ll lose her license for five years.

The police report had misspelled her name, but I was nonetheless able to find her Facebook page. She lives on a small horse ranch in Willcox, AZ, with her husband and three small children. She’s a rodeo barrel-racer, a big Trump supporter (naturally—this is rural America we’re talking about), and a critic of people who give children horse-riding lessons without carrying proper insurance (a subject I’ll get to in just a bit). While scrolling through her timeline, I noticed that in early December, she had posted a flyer advertising a rodeo in Wickenburg that would begin on December 18th, the day before our paths crossed on Highway 74. There’s really no question the police have the right woman, though she’s apparently still denying it. (She has since made her Facebook page private.)

As you might imagine, the coverage provided by her auto insurance policy is of great importance to my lawyer and me. Unfortunately, Arizona has weak standards for auto insurance, and her truck is only insured for $25,000. The horse trailer, however, is owned by her in-laws in Utah; my lawyer is inquiring to find out what it’s insured for.

Fortunately for me, as if by some miracle, Blue Cross Blue Shield has paid all of my medical bills—over $100,000 and counting—minus my policy’s small deductible, so I’m only on the hook for about $5,000. (Whew! Once again, praise the heavens for Obamacare.) Naturally, my lawyer is preparing to argue that I should be entitled to “pain and suffering” compensation exceeding that amount. We’ll see what happens. I don’t have my hopes up; I’m presuming I won’t get much more than my out-of-pocket and missed-work expenses (about $10,000–$15,000 all told, I calculate).

Adventure Cycling’s detour through Yuma

One last detail I’ll mention: When I started my trip, after leaving Los Angeles I dipped sharply southward, hugging the Salton Sea on my way to Brawley, CA. I did this to hook into Adventure Cycling’s “Southern Tier” route, which stretches from San Diego to St. Augustin, FL. As you’ll remember, I’d never ridden cross-country before, so I thought it would be wise to take this recommended path. My roommate Steven, who had followed a different Adventure Cycling route (the “TransAmerica Trail”) on his cross-country trip, seconded this plan.

Following the Southern Tier route, I curled back up to Blythe, CA, by way of the windy (with both a short and long “i”), hilly, and frankly rather dangerous Route 78. Next it had me pass through Salome and Wickenburg, AZ, then onto Highway 74 heading into Phoenix.

By peculiar coincidence, on February 8, I got an email from Adventure Cycling with the subject line “Major Detour on Southern Tier Section 1.” “This detour avoids the winding, narrow, and hilly SR 78, and the associated truck and recreational traffic hazards between Brawley and Blythe, CA,” said the email. The new route (shown above) mostly follows Interstate 8 through Yuma and on into Gila Bend. On the one hand, this would’ve been a much quicker route to Tucson; on the other hand, these are, ahem, not the most scenic parts of Arizona. it would’ve been a boring and unpleasant straight-shot slog, hundreds of miles on the shoulder of a large, busy interstate.

In other words, if I’d begun my trip two months later than I did, I would never have had the 97-mile ordeal on California State Route 78 that turned out to be, by far, my most memorable day on the road. I wouldn’t have seen the beautiful Cibola National Wildlife Refuge, or encountered John, the self-taught loner, in a Salome campground. And I would’ve missed a fateful, life-changing morning on Highway 74. Funny how the universe plays its hand!

August 19, 2021: Eight months after the crash, I am humbled. My surgeon in Phoenix, Dr. Farhad Darbandi, had told me I would be “walking in six months, and back to normal in a year,” which I took to mean I’d be ambling all over Durham by the summer, and by Christmastime I’d be back on a bike, and going on my cherished five-mile runs. I was optimistic and gung-ho, exercising and knee-bending enthusiastically. I thought I would beat Dr. Darbandi’s timeline and slide right back into my active life.

That hasn’t happened. In March, when I took my first steps without crutches, I never guessed I’d still be using them in August. I can walk without them now, just not particularly well, nor very far. My right leg is still weak and stiff, which makes it hard to walk normally, and it gets tired quickly. Building back atrophied muscles is hard work! And unlike exercising fit muscles, it’s not in the least enjoyable.

I had assumed that my love of exercise and fitness would get me through this recovery ahead of schedule, but the process simply cannot be rushed. In fact, I suspect that my assiduous exercising was actually slowing my progress, because my muscles couldn’t do what I was asking them and they needed more time to rest. I’ve learned this lesson the hard way, through pain and disappointment. I believe I’ve found a sensible middle ground, each week indulging in a three-mile crutch odyssey and a few shorter trips, while being sure to take it easy the other days. Patience!

On a positive note, yesterday I took my first crutch-free walk around the block. It was a lot harder than I expected, more of a slog than a stroll. But I was able to grit my teeth and get through it, in the hope that it will be easier next time. I immediately iced my knee when I got back to the house, and today my leg feels fine. Progress!

X-ray from June 2021, before the second surgery

On a more negative note, last month I had a Zoom call with Dr. Darbandi, and he said the newest x-rays show that my femur is not healing: The millimeter gap of the break is not being bridged. He said as far as he could tell, I have three options: Wait and see if it starts to heal on its own; remove some of the screws holding the bone and rod in place, allowing the two halves of my femur to move slightly closer together; or remove the titanium rod running through the center of the bone and put in a new one. That last option was definitely my least favorite, because it sounds like starting my recovery over again from square one.

I wasn’t going to fly back to Phoenix for surgeries, so Dr. Darbandi said I should see a surgeon at a big teaching hospital, like Duke or UNC. My primary care nurse got me an appointment at UNC Medical Center (which takes my insurance), and this week I met with an orthopedic surgeon, Dr. Andrew Chen. He gave me the bad news: Because the rod in my femur projects slightly into my knee joint, we should not just take screws out—this might cause the rod to scrape cartilage off my patella. He strongly recommended replacing the rod.

I thought of the excruciating months I’d struggled just to bend my knee, and shuddered to imagine starting from scratch! But he reassured me it wouldn’t be at all like the surgery in December, and I should recover quickly. He’d use the same one-inch incision at the front of my knee (modern medicine is rather miraculous!) to take out the rod and put in a new, thicker one, which should stimulate bone growth to get my femur back on track. This surgery will probably be scheduled for September.

Finally, on the legal front: The company that insured the infamous horse trailer has refused to answer my lawyer’s questions, and they deny that their client is in any way culpable. My lawyer has teamed up with a larger Phoenix law firm, and they’ve filed suit on my behalf. This was months ago, and there have been no new developments since. My lawyer says that, like my leg injury, the operative word here is patience. “Buckle in,” he said. “This could take years.”

April 14, 2022: A lot has happened in eight months!

First, on the legal front: I recently got a call from a lawyer in the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office. He told me they won’t prosecute for hit-and-run; while the police investigation was centered on that charge, they ended up declining to file it, apparently because it would be hard to prove the driver had knowingly left the scene. The police did ask for a charge of making false statements, a misdemeanor, but it’s been over a year and the statute of limitations kicked in, so she won’t be charged with anything.

It seems clear to me that she knew her wheel hit me, and knowingly fled—why else would she have made up a story? All this time I had assumed she would pay a penalty for hitting-and-running. I thought there might be a trial, which I would’ve liked to attend. And even though I never felt too personally outraged about her actions, since the lifesaving care I got from Heather the nurse meant it wouldn’t have affected me much if the driver had stopped to check on me, I’m a little troubled that she’ll have no consequences at all.

Oh, except she did volunteer to give me $2,000. Add that to her state-minimum $25,000 car insurance policy—turns out the insurance on the horse trailer didn’t cover injury—deduct my lawyers’ 40%, and that leaves me with about $16,000. Fortunately Blue Cross/Blue Shield made good and paid all of my $150,000 medical bill, so I was really only out a few thousand dollars for the deductible. Now, I will admit, for a while I entertained fantasies of six-figure payouts. (Hmm, I could buy a house in central Durham, and/or take a two-year trip around the world…) So it was a mild letdown to hear the final number. And hearing about friends who got many tens of thousands of dollars for substantially lesser injuries has been a little irritating. But I don’t feel I deserve, or am owed, a pile of cash for my broken leg, so I really have no complaints.

As for my physical recovery, it’s been painfully slow but always moving in a good direction. The surgery in September to replace the femur rod went well, and x-rays show the two halves of bone are finally starting to knit together. All that’s left is to get the muscles back to full strength and hope the tendons and ligaments work themselves out.

At the end of the American Tobacco Trail, halfway through a 50-mile ride

I still hobble a little or a lot when I walk, because strengthening weak leg muscles taxes them and makes them feel tight, which cramps my stride; whereas if I relax and hardly use my leg for a couple of days, it feels great, but that means I’m not building strength. It’s two steps forward, one step back. I have to zoom out and look at the changes month by month to see the gradual improvement. My goal for 2022 is to be able to run again, but I’m still a long way from that.

The best news regarding my recovery is that I finally got back on a bike in mid-February. At first it was a little difficult, which gave me empathy for beginner cyclists who complain about hills (you have to keep at it for a few months until your legs get strong enough that you barely notice them). Biking is a lot easier than walking, so once I could comfortably go ten miles in a day, I quickly ramped up the distances: 20 miles, then 30, then 40. On my birthday in late March, I went 50 miles down the American Tobacco Trail and back.

My next target is 60 miles, and then, a month from now, a larger goal: A two-day, 125-mile ride from New York to Philadelphia, a fundraiser for the East Coast Greenway Association. I’ll also be raising funds for Bike Durham, the powerhouse nonprofit whose board I currently chair. (We’re really on a roll—this month we were named Advocacy Organization of the Year by the League of American Bicyclists, and a week later we received a $480,000 contribution from an anonymous donor.)

This ride will be a sort of official comeback for me, after a long and sometimes grueling year and a half of recovery. Some people I know thought I might never be able to walk normally again, that perhaps I should start using a cane; I’ve refused to accept that I’ll be anything less than 100% of what I was, which I think has helped my recovery. Sure, it’s possible I won’t regain every last drop of my previous capabilities, but I’ll fight like a tiger to get as close as I can, and however far I do get, it’ll be because I pushed and fought (intelligently I hope!) and didn’t give up.

The GoFundMe for the ride is here. Wish me luck!

Comeback Ride! NYC–Philly 2022

Day 1 (May 14): After a couple months of training that culminated in a series of 60-mile rides, I’d come to this pivotal test: Could I pedal 125 miles in two days? I admit I was nervous! I hadn’t yet gone 75 miles in one day, much less turn around and go another 50 the next. I flew to New York three days before the ride and stayed with my friend Steve in the East Village, resolved not to walk much—a kind of torture in ultra-walkable Manhattan!—so that my right leg would be fresh for the trip. But each day it felt tighter, and my stride got worse. I really didn’t know if I could make it. At least the weather was cooperating: The forecast was overcast skies with no rain and temperatures in the 60s, perfect for midday biking.

The ride’s start, with nearby Jersey City buildings visible through a fog that swallowed Manhattan

Saturday morning dawned with a pre-odyssey odyssey: Just to get to the starting line in Jersey City’s Liberty Park, I had to wake up at 5:45 a.m., take a subway (the L), to a commuter train (the PATH), to light rail (the Hudson-Bergen line), then walk a half-hour with all my luggage. I plodded to the staging grounds with time to spare, and folks from the East Coast Greenway Alliance (conveniently based in Durham!) helped me find my bike, which they had graciously arranged to haul up in their trailer. After opening remarks from the organizers, I joined 200-some-odd riders raring to go on a morning so foggy, we couldn’t see the Manhattan skyline or the Statue of Liberty just a few miles distant.

I pedaled gingerly, cautious about my leg, but trepidation gave way to delight as we glided over boardwalks and footbridges in the morning mist. As we headed into Jersey City, then down through Bayonne, I felt an echo of the euphoria I experienced on my first day cycling through Los Angeles in 2020. There’s a mysterious multiplier effect when trekking by bicycle; riding a bike is fun, and so is traveling, but when you combine the two you get a sum greater than its constituent parts.

This was my first supported group ride, and I soon discovered that as the line of cyclists spreads out to a linear graph of average speeds, they stick together in clumps for safety and camaraderie. I found myself chatting with a small cohort of easy-pedaling cruisers, including folks from Boston, New Jersey, and Connecticut, united by our preferred travel speed. About ten miles in, we arrived at the foot of the Bayonne Bridge, which welds New Jersey to Staten Island. It’s very tall—217 feet above the water, a lot higher than the Brooklyn and Manhattan bridges I used to cross when I lived in New York. I eased into the long uphill, keeping my pledge to pedal slowly, but soon my hill-attacking instincts welled up. My right leg was starting to feel good. I hit the gas..

Waiting for a red light at a random intersection in Iselin, NJ (a heavily South Asian area—delightful curry aromas wafted through the neighborhood)

The view from the top of the bridge was spectacular, with ships plying through the fog far below. I started downhill, pumping my brakes all the while—since my crash, I’m averse to bombing hills. Soon I was coursing through the streets of Staten Island with a faster clump of riders than before. No greenways here; this was city cycling, a mix of neighborhood and arterial streets that would account for most of the first 50 miles.

My leg continued to feel great, so I continued to pick up speed, advancing from one clump of riders to the next. The clumps became less chatty and more male, though I was cheered to see, among the speedier riders, 60- and 70-something women who were fast, fit, badass bicyclists.

By the time we stopped for lunch, about 50 miles in, I knew I’d have no trouble finishing the day. At that juncture, we could choose to get off of roads and onto the D&R Greenway, a gravel and dirt trail that girdles the skinny part of New Jersey. My bike’s hybrid tires are fine off-road, so that was my choice.

…which was great at first, a serene jaunt along a canal, lush with overhanging trees and flecked with ducks, geese, turtles, and heron. But then it started to rain, lightly, then more heavily. I normally avoid riding in the rain—as long as it’s not too cold, the experience itself is not unpleasant, but you usually don’t want to arrive where you’re going soaking wet. Today, though, I knew there was a warm, dry hotel room at the end of the trail, so getting soaked was kind of fun. There were just two drawbacks: 1) You had to ride slowly and carefully through and around slippery lagoons that sometimes spanned the trail side to side; 2) The bike I rode in 2020 had fenders, but I had so far neglected to put them on this, my former guest bike. Which meant my rear wheel kicked up watery mud that splattered my bike and my person until we were a thickly daubed, brown, sticky mess.

The D&R Greenway before the rain

The greenway mid-drench

So much for the no-precipitation forecast, which did hold up for New York City, just not central New Jersey. After some seven hours of cycling, by the last five or ten slow, soggy miles, I was kind of done. Arriving at the Princeton YMCA to a steady light rain, we lined up to hose mud off our bodies and bikes. I helped myself to leftovers from lunch, and a friendly volunteer named Chuck gave me a ride to the Princeton Doubletree, where I spent an hour and a half rinsing mud out of my clothes and drying them with a hair drier. I felt sweetly exhausted and newly capable, without limits, at least for one day—for sure I could’ve gone another 25 miles if I’d had to. I also felt a mix of admiration and pity for the hardy souls who pitched tents and slept on the sodden grass field at the Y.

Day 2: I woke at 6 a.m. to another glorious foggy morning, temperatures still in the 60s. The rain had stopped. Chuck gave me a ride back to the Y. I glopped on sunscreen, and would do so again a few hours later as the sun chased away the clouds. We ate breakfast and pushed off a little after 8. I found my 13-mph “tribe” and settled in to a brisk pace. I wasn’t sure how my right leg would hold up on a second straight high-mileage day.

I should mention here a key benefit of this supported ride: The hundreds of directional signs telling us where to go. The organizers had spent days laboriously laying out the route via innumerable little yellow arrows affixed to trees and telephone poles, and signs saying things like “Ride single file,” “Turn ahead,” and “YOU MISSED THE TURN.” No need to consult maps or your phone. What a luxury!

I wasn’t very chatty this day. My focus was inward, as I listened to muscles and joints to sense how hard I could push. My right leg gave an “all clear,” so I decided to push hard. At the next-to-last “oasis” (the organizers’ name for water/snack stations), I arrived with a pack of riders, gulped down water and a banana, and headed out on my own to see how fast I could go solo. It took me one hour to go 15 miles: slower than my pre-crash maximum, but not by that much. It felt amazing to reach that pace 100 miles into our trek.

I pulled into the last oasis feeling great, but the clouds were parting, the noontime sun was beating down, and I wanted to hurry to the finish line. According to my mental calculations, there were around ten miles left. I asked the volunteers staffing the oasis for the exact mileage. “Only 22 miles to go!” they said. Huh.

I checked my phone, and Google said it was 10 miles by bike to the finish at Penn’s Landing, where a lunch of vegan cheesesteak awaited. To be sure, Google’s route was likely more direct than the Greenway, which will often go out of its way to access safer, more pleasant thoroughfares. But ten miles versus 22 is a big difference!

A staffer showed me the route on his phone, and I saw that one source of the discrepancy was a circuitous loop near the end of the ride. We were supposed to quit a waterfront bike path to wind a five-mile circuit through the streets of downtown Philly. Ordinarily I wouldn’t turn down a good sightseeing detour, but I didn’t want to glop on more sunscreen, or spend an extra half-hour dodging traffic, and now my butt was starting to hurt from hours in the saddle. 125 miles was quite enough, thank you very much!

The end! For now.

I headed out for the final stretch with about a dozen riders. They were all game for the circuitous loop (though even before we got there, one woman remarked, “It feels like we’re going in circles”), so when we got to the critical juncture, I said “See ya!” and scooted off to Penn’s Landing.

Ten minutes later, I crested a ramp to the top of the park, rolling in to welcome applause from a small group of volunteers. I felt delightfully spent. My Philadelphia friend Eleni was there to greet me (her husband Rob was at home with COVID), bearing a delicious pastry. It was 1 pm on a magnificent spring day, and I’d just proven to myself that, vis-a-vis distance biking, I can almost consider myself fully recovered. Triumph.

I dropped off my bike with ECGA staff, who were kind enough to haul it back to Durham in their trailer. I retrieved my luggage and walked a couple miles to my friend Kelly’s Center City apartment, where I had a long shower, a rooftop nap, and, later, a well-deserved rest.

Final thoughts: This comeback bike trip won’t be my last. Distance biking has been life-changing for me, not just for the lessons learned in overcoming adversity occasioned by my injury; more meaningful has been discovering a new source of challenge and joy.

For now, though, my focus is on getting my right leg stronger as quickly and efficiently as possible, which means shifting from distance biking to weight training. I hope to be able to run again by the end of the year. I’d love to get back to five miles in 37 minutes, but at this point I’ll take what I can get!

Thanks to generous friends and family, I was much heartened by the success of my comeback-ride fundraiser, with $5,530 to split between the East Coast Greenway Alliance and Bike Durham. I’m evangelizing to Bike Durham’s board and staff to ride NYC–Philly 2023 as a team.

Oh, and one last update on my legal case: My lawyer called yesterday to report that the woman driving the truck towing the horse trailer, who had committed to personally paying $2,500 in reparations, has gone AWOL. The GEICO lawyer suspects she and her family may have been planning to move, and decided the timing worked out to sneak off and avoid this obligation. Not surprising, in light of her previous actions. But no matter. I’m taking my small insurance settlement and going on a 2 1/2-month trip to Europe this fall. All’s well that ends well!